A post by editor and author Michael Bracken over at Sleuthsayers last week made me ponder my writing influences when it comes to detective fiction. Michael, who has read more than his share of detective fiction in the course of his work recently, suggested that authors need to move away from the trope of the “broke, drunk, and horny” private eye if they want to write something that stands out from the pack. He also recommended not always starting the case in the detective’s office because that can lead to too much back story and a severe delay in moving the plot forward. Reading his post, I realized that I’ve never once had the urge to write that stereotypical “broke, drunk, and horny” character. Then, I wondered why I hadn’t.

My first published short story was a detective story. And while my character, a private investigator named Pete Lincoln, was broke, his financial situation had more to do with the times in which he lived than with his own inability to manage funds. His sex life was irrelevant to the case and didn’t come into the story at all. If he drank, it wasn’t to excess, and also didn’t come into the story. Pete lived and worked in a future world in which privacy rights didn’t exist. He appeared in a story entitled “A Reasonable Expectation of Privacy,” which was first published in Analog: Science Fiction and Fact in 2012, and reprinted in Black Cat Weekly #19 in 2022.

Given that most writers, when they first start crafting fiction, write the tropes that they absorbed while reading, I asked myself what detective fiction I had absorbed at an early age that influenced my writing and that didn’t lead me straight to writing the classic stereotype that Michael was lamenting. Who was the first fictional private detective that I read?

And the answer came to me: Encyclopedia Brown, Boy Detective.

While the boy detective did teach me the basics for detective fiction, he wasn’t in financial straits since he was a child who lived a quite middle-class life with his parents. Everyone knew Encyclopedia liked his friend and partner Sally, but that didn’t remotely approach the trope of womanizing detective. As for drunk, no! While some of his cases started in his garage office with a client paying the twenty-five-cent fee, other times Encyclopedia solved cases for his father, the police chief, while sitting at the family dinner table. So the stories also taught me that not all cases had to start in the detective’s office.

By the time I read Sherlock Holmes a few years later, the pattern of how detective fiction worked was already firmly fixed in my head. While Holmes indulged in illicit substances, he also wasn’t a classic “drunk.” Holmes never panicked about paying the bills or complained about being broke. As for women, the only one that counted for anything for Holmes was Irene Adler. So Holmes, another of my early fictional detective influences, didn’t fit the stereotype either.

Since writing my first PI story, I’ve written many other detective stories. While I have started several of them in the detective’s office with the arrival of a client, not one of my detectives has been “drunk, broke, and horny.” For example, Detective Maya Laster is a former middle school teacher who turned a genealogy hobby into a detective business, solving mostly cold cases with the help of forensic genetic genealogy. She has appeared in two stories in Black Cat Weekly (issue #79 and #110) and will be appearing again in an upcoming anthology.

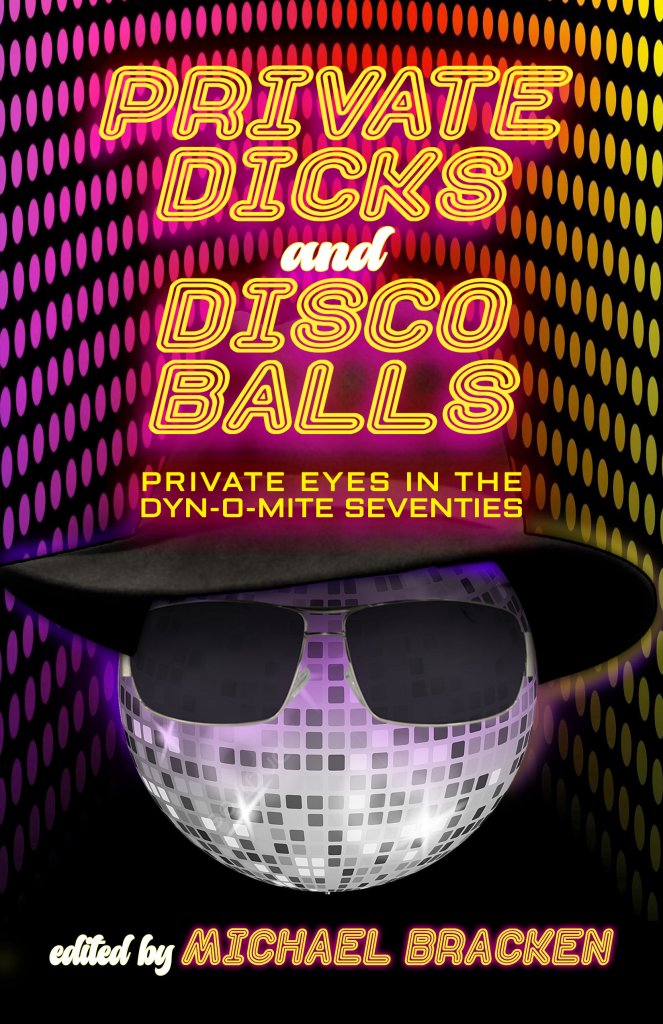

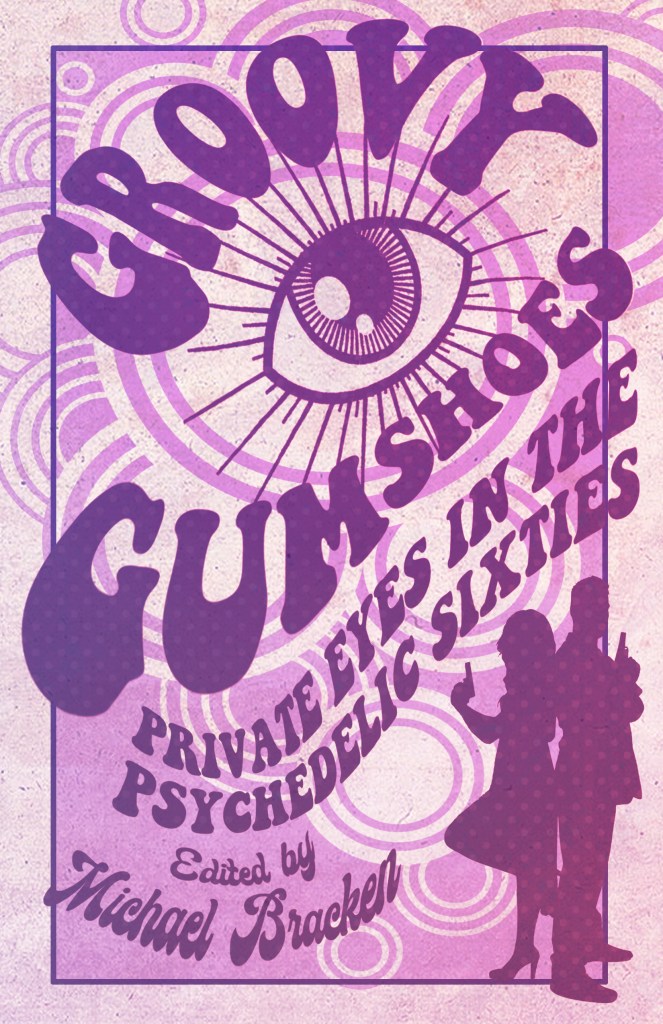

Another of my characters, PI Jerry Milam, came of age during World War II, became a police officer following the war, and suffered terrible injuries in a car wreck which ended his police career, leading him to become a private investigator. He’s a teetotaler with a solid income and chronic left hip pain who feels he missed his chance with women. He appeared in Groovy Gumshoes: Private Eyes in the Psychedelic Sixties and Private Dicks and Disco Balls: Private Eyes in the Dyn-O-Mite Seventies. One of my current works-in-progress sees him solving a case in the 1950s.

If my detectives managed to side-step the cliché of the “broke, drunk, and horny” private investigator, I have my early reading influences to thank for it. So thank you Donald J. Sobol for creating Encyclopedia Brown and teaching me to create private investigators who avoid falling into clichés.

*****

N. M. Cedeño is a short story writer and novelist living in Texas. She is active in Sisters in Crime- Heart of Texas Chapter and is a member of the Short Mystery Fiction Society. Find out more at nmcedeno.com.